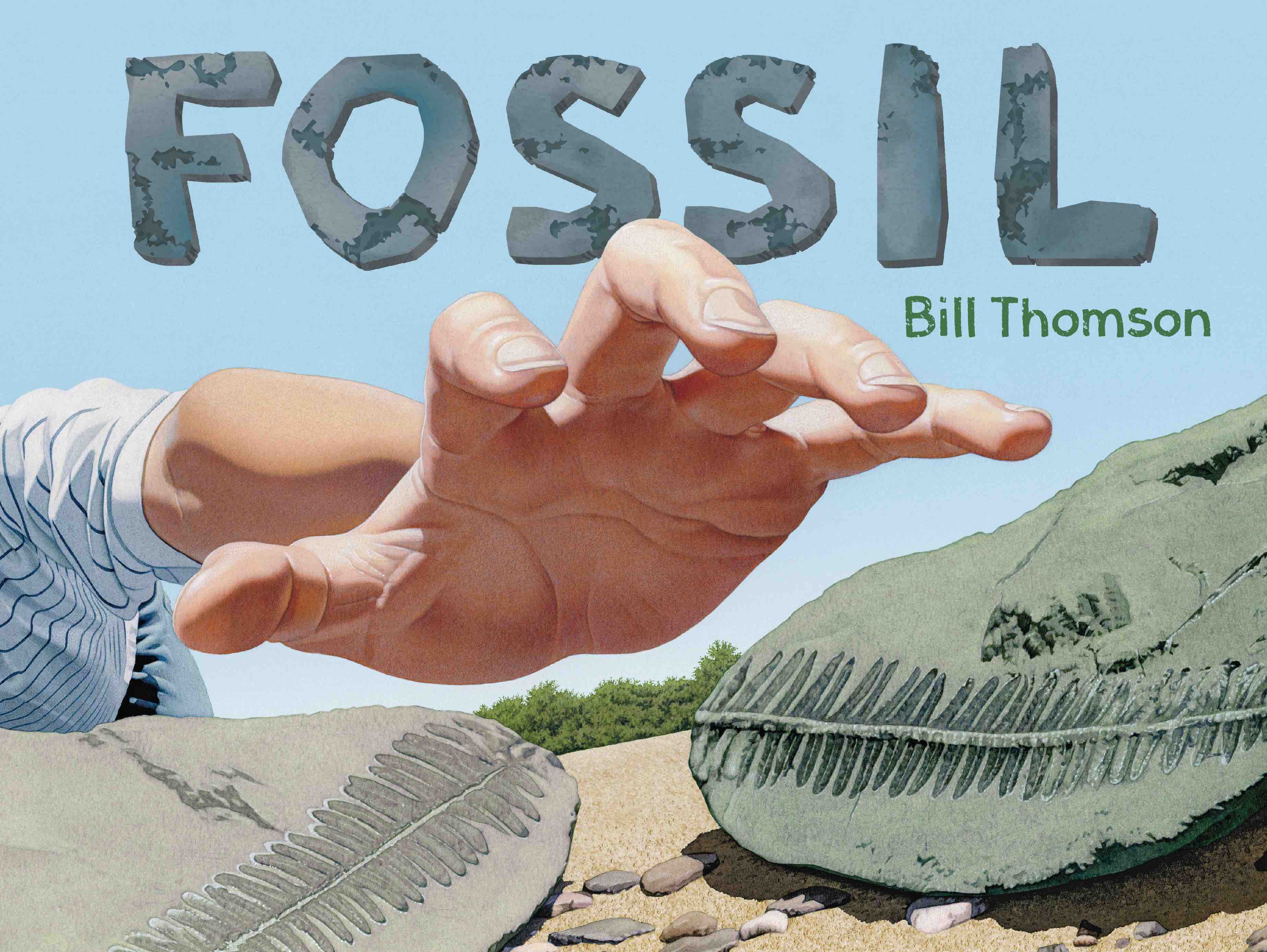

Bill Thomson is the creator of “Chalk” and “Fossil.” He is also a professor of illustration at the University of Hartford. The following is a complete transcript of his interview with Cracking the Cover for his latest book, “The Typewriter.”

Bill Thomson is the creator of “Chalk” and “Fossil.” He is also a professor of illustration at the University of Hartford. The following is a complete transcript of his interview with Cracking the Cover for his latest book, “The Typewriter.”

You haven’t always worked as a children’s book illustrator. What made you move in that direction?

After working for nearly twenty years as a freelance illustrator creating advertising artwork for clients across the U.S., my life changed dramatically when I accepted a university faculty position teaching illustration. For the first time in my life, I had the freedom to pursue work that I loved and not that which offered my family the most financial security. As the father of three boys who enjoyed children’s books as an integral part of their childhood, I was determined to pursue children’s literature. It took three years, but I accomplished that goal with the publication of my first children’s book, Karate Hour (2004), written by Carol Nevius. I absolutely cherish the opportunity to entertain, engage and inspire young readers through my work—I can’t think of a better way to use the talents God gave me.

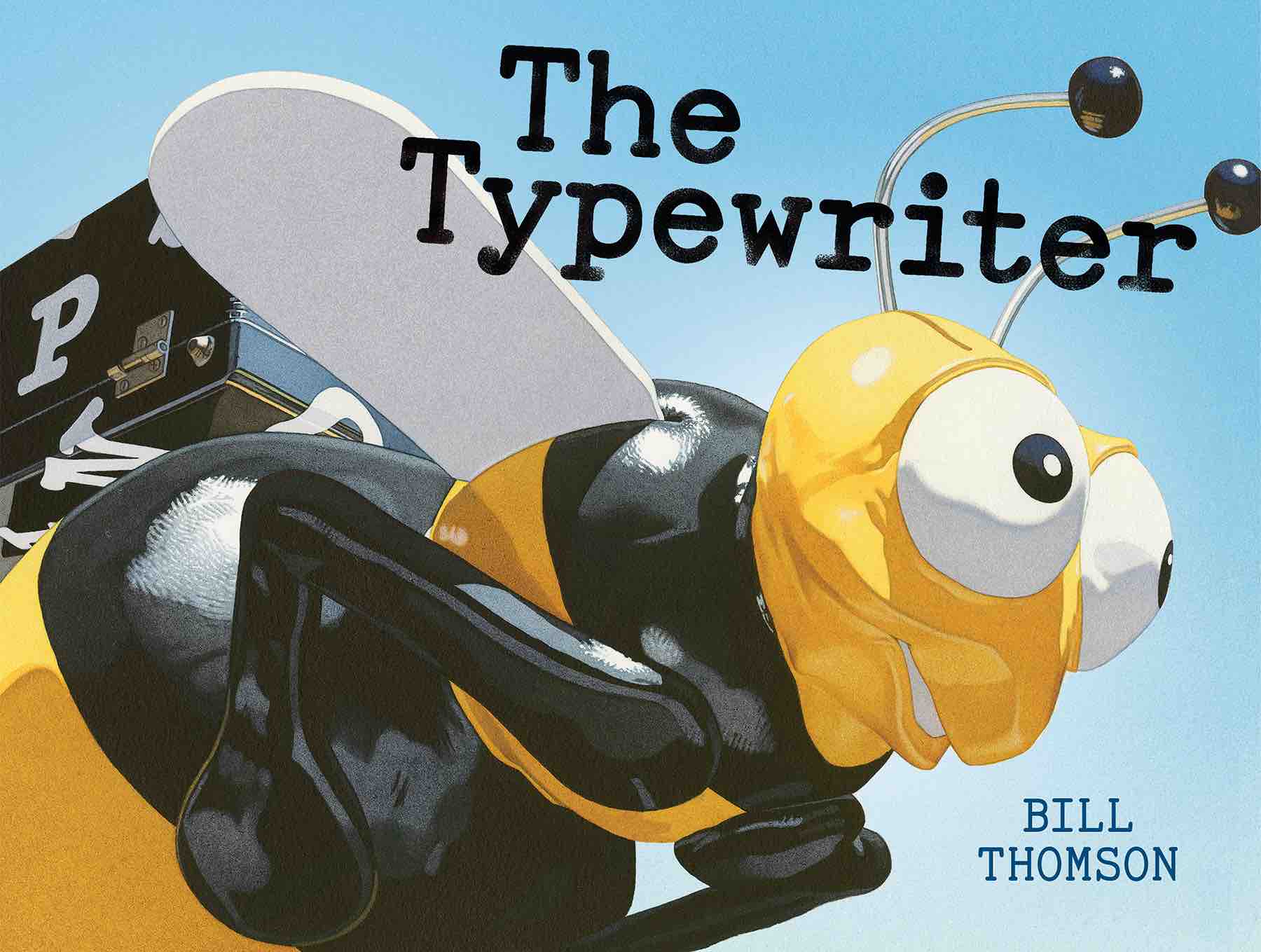

Where did the idea for “The Typewriter” come from?

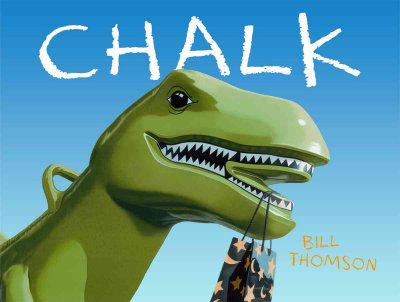

The Typewriter completes a trilogy of wordless books that apply imagination to different elementary school subjects. In the first two books, Chalk applied imagination to art and Fossil blended imagination and science. The Typewriter celebrates the power of words and fuses imagination with writing in a thrilling visual adventure. I initially wanted to create a book that explored writing, but I wasn’t sure of what my approach would be. Then one day I was answering emails and looking at my keyboard. I considered how quickly digital technology has become the norm in our lives, and how many children are probably not even aware of typewriters. I began researching vintage typewriters and wanted a model that could easily be handled by a child, but would also be visually interesting. I discovered the Underwood Universal Portable Typewriter (1930’s) and bought a beautiful one on eBay. I refinished the beat-up carrying case with a reflective surface and letters adorning the exterior to make it magically captivating. In addition to making readers appreciate the limitless power of words, I hope this book will also generate discussions about writing instruments that were used before keyboards and screens.

Why are books like “The Typewriter” important?

Why are books like “The Typewriter” important?

Wordless stories like The Typewriter require reader participation and offer the opportunity to create a unique narrative, interpreting what is seen in the illustrations and informed by each viewer’s life experiences. This allows young readers to develop an understanding of story structure, establish characters and settings, and hone prediction, sequence and inference skills. Working realistically, I also hope to make the incredible seem believable and engage readers in my visual stories. Creating The Typewriter was a true labor of love and I spent more time on this book than anything I have ever done. I painstakingly painted every detail of the machine to clearly show its structure and operation. I really hope that young readers enjoy The Typewriter and teachers find it be a useful classroom tool!

The only words used in “The Typewriter” are those that are actually typed. Why did you decide to make the book illustration only?

As I mentioned, this is the final chapter in a trilogy of wordless books, so I wanted consistency throughout the series. A magical Monarch butterfly (created in Chalk) links the three adventures. The Typewriter intends to foster creativity and encourages young readers to view words and writing as fun and powerful tools. I should also note that I drew all of those typed words by hand (very tedious work), so that all three stories are told purely through illustration.

How do you approach writing/illustrating a book? What’s your process?

How do you approach writing/illustrating a book? What’s your process?

My books start with a written synopsis. After developing a storyline, I draw out thumbnail sketches, trying to present the story in an interesting way. Without the support of words, the illustrations need to be clearly and easily understood by young eyes and minds. Because I want readers to accept fantasy as plausible, I work very realistically. It is critical that everything is presented equally convincingly—if one thing is off, the entire illustration will lose credibility. For The Typewriter, I took nearly 12,000 photographs that provided me with visual information for everything seen in the book. Looking at the best elements from many photos, I create a very precise pencil drawing with every aspect of the illustration worked out. Then I paint a monochromatic under-painting to establish all of the values. Then I glaze color on top with acrylic paint. And finally, I go over everything again with colored pencils. I took a sabbatical from teaching, and painted The Typewriter at least fourteen hours every single day for a full year. Each illustration took between 125 and 150 hours to paint, and I spent more time on this book than anything I have ever done.

What do your own kids think about your work? Do they ever offer any suggestions?

My sons have modeled for illustrations in my books, and more importantly, have been instrumental in the direction of my children’s books career. As a father, I especially treasured their younger years and enjoyed rediscovering the world through their eyes. I wanted to make books that I thought would appeal to kids like them. My youngest son, Ethan, was critical to my creation of wordless books. A few years ago, he brought home a wonderful story that he wrote in elementary school. Ethan did an extraordinary job, so I asked him where he got his idea. He explained that his teacher gave the class a “writing prompt” to read and each student crafted their own story from there. Seeing the impact that stimulus had on my son, I wanted to create books that would not only interest young readers, but could also be used as educational tools as well. I envisioned creating a visual prompt that could build confidence for beginning or reluctant readers, serve as a writing prompt for older children, and possibly be a launching point for creative activities or discussion. That father/son discussion directly led to the creation of Chalk and the wordless imagination-based books that followed.

What is it about your work that appeals to kids?

What is it about your work that appeals to kids?

I think that answer might vary with each reader, but I try to create stories that my own children would have liked. I also try to include things that kids can relate (carousels, ice cream, etc.) to establish a level of familiarity before transitioning into the fantasy. Along with the bold images, I hope this engages kids and makes them feel like participants in the story.

What are you working on now?

After taking several months to recharge, I am just now beginning to develop future story ideas.

Is there a book from your own childhood that still resonates with you today?

For me, The Giving Tree will always represent the gold standard of what a children’s book can be. The selfless message of love that Shel Silverstein so beautifully presents was inspiration to me then and continues to be today. I just love that book.