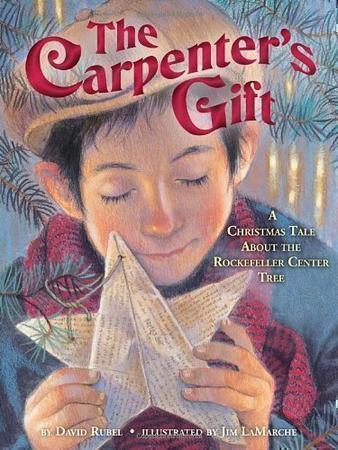

David Rubel is the author of “The Carpenter’s Gift.” The following is a complete transcript of his interview with Cracking the Cover.

How did you become involved with “The Carpenter’s Gift?

After writing If I Had a Hammer: Stories of Building Homes and Hope with Habitat for Humanity in 2009, I traveled to Thailand for the annual Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Work Project. This was my first volunteer experience with Habitat; and even though I knew what to expect from the research I had done, there is still a big difference between listening to a description of a rollercoaster ride and taking the plunge oneself. My experience in Thailand turned out to be just as thrilling as advertised, and it awoke in me feelings that I knew would be difficult to express in another work of nonfiction.

A few days after my return, I sat with my children as they watched the annual lighting of the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree on television. I already knew from my research that for several years Tishman Speyer, the owners of Rockefeller Center, had been donating lumber from the tree to build Habitat homes. Thinking about this remarkable gift, I realized that it could serve as the perfect touchstone for a different kind of story about the emotions that involvement with Habitat evokes.

How much of “The Carpenter’s Gift” is fact and how much is from your imagination?

Because in my other life I’m a historian, I researched the origins of the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree tradition as much as I could. I spoke with Dan Okrent, whose Great Fortune is the definitive history of Rockefeller Center. I also visited the Rockefeller Center archives. I think it’s fair to say that, as a result of this work, I’m one of the world’s leading experts on the history of the tree—although it’s probably more meaningful to say that I’m one of the world’s only experts.

There actually is not much to learn because very little is known. The first tree was erected in 1931 by construction workers digging the foundation of Rockefeller Center, who pooled their money to buy the tree. We don’t know who collected the money or where the tree came from, but we do know that its purpose was to express the workers’ gratitude at having jobs when so many other people were out of work because of the Great Depression. We also know that the tree was decorated with garlands and other ornaments handmade by the families of the workers.

Everything else came from my imagination; but because I held close to what is known, I prefer to think of The Carpenter’s Gift as an origin myth rather than simply a work of fiction. Nothing in the story really contradicts the known facts, so it could have happened that way. Wouldn’t that have been nice!

What were the challenges of telling this story?

What were the challenges of telling this story?

The biggest challenge was fitting what is a relatively complicated story, taking place over many decades, into the picture-book format. My adult books run into the many hundreds of pages, and even my children’s books usually run 100–200 pages. Working with just 48 pages, and with so few words on each page, forced me to be superefficient. I started with a first draft that was about twice as long as the space available, and then I began paring. First I cut out every action that wasn’t essential, which helped. Then I thought about how I could roll two scenes into one. Finally, I went through the text, examining each paragraph, word by word, to see what else I could cut. I lost track of the number of drafts I went through at a dozen. At that point, I was maybe halfway through.

This is your second book collaboration with Habitat for Humanity. Why partner with that charity?

One of the best things for me about working with Habitat for Humanity is that I am a complete convert to the Habitat way of thinking. What makes Habitat different from other philanthropies is that it doesn’t give homes to people but helps families in need build homes for themselves. It’s a hand up, not a handout, as the Habitat folks say. Similarly, while Habitat certainly accepts donations from people with resources, what the organization really seeks to do is get people involved beyond the writing of a check.

When I was researching If I Had a Hammer, I was able to spend some time with President Carter, and one thing he told me that I’ll never forget concerned the “chasm” that exists between people with resources and those without. No matter how hard someone like you or me tries—even someone like himself—it’s impossible, he said, for a single person to bridge the chasm that exists between the haves and the have-nots. The economic, social, and experiential differences are just too great. But that’s where Habitat comes in, providing the bridge that allows people from all walks of life, those with resources and those without, to come together as fellow human beings. I’m not religious in the same way as President Carter, but I completely agree with him when he says that coming together in this way allows everyone to be “redeemed.”

Everyone who has worked on a Habitat build knows this to be true. One of the people I interviewed for If I Had a Hammer, a Habiholic named Tom Gerdy, told me that he’s been busting his butt for years trying to give back more than he’s gotten from his work with Habitat—and he still hasn’t been able to do it. I think that’s how many volunteers feel about their work with Habitat.

Have you helped on any of the builds?

My wife, Julia, joined me on the Carter Project in Thailand, and after we got back home, we both volunteered with our local affiliate. My wife became the volunteer coordinator for a time, and I helped her with that work; but we’ve both now scaled back to just construction work. Because our schedules are flexible, we can help out during the week, when mostly the regulars are around. The camaraderie is great, and we try to volunteer every week, though sometimes other commitments can get in the way.

What I find most rewarding about the experience is that I’m directly connected to what’s going on. I work with and get to know the family that will own the house, and I can see how building their own homestead exhilarates them and grounds them more firmly in the community.

What do you hope readers bring away from this story?

What I hope is that fifteen or twenty years from now, a young man or woman will show up to volunteer on a Habitat build site. At some point—during lunch, maybe—one of the other volunteers will ask this eighteen-year-old why he or she decided to volunteer. “Well, it’s interesting you should ask,” the eighteen-year-old will say. “The reason I’m here now is that when I was young, my parents used to read me this book called The Carpenter’s Gift.”