“Why do I write? One might as well ask me why do I breathe.” — Karen English

“Why do I write? One might as well ask me why do I breathe.” — Karen English

Once upon a time, Karen English taught elementary school. Now, she writes books for young readers. The two, she says, are symbiotic.

“I think teaching has given me a heightened sense of empathy,” Karen told Cracking the Cover. “I think I can see beneath the surface of young people’s behavior and their occasional resentments and frustrations. Teaching has given me a kind of window into their challenges. And that leads to more story ideas.”

Years of teaching school and being the mother of four children have given Karen insight into the hearts and minds of young people. “My goal is to write stories that reflect those hearts and minds and situations with which young people are often confronted,” she said.

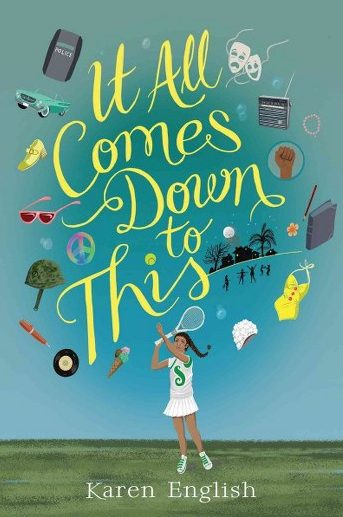

Karen’s latest book, It All Comes Down to This, takes place in 1965 Los Angeles. Twelve-year-old Sophie is the new black kid in a mostly white neighborhood. All she wants to do is write her book, hang out with her new friend, Jennifer, and star in the community play. But things aren’t so easy — her sister is about to go off to college; her parents’ marriage is on the rocks; and their new housekeeper is anything but nice. When riots erupt in nearby Watts, Sophie learns that life is even more complicated than she’d once thought.

The idea for It All Comes Down to This was inspired by a comment a housekeeper made when Karen was a child.

“She told me that if I ever went to Africa, the Africans would kill me. ‘They don’t like no light skinned Negroes in Africa,’ was her assertion. One of my goals was to write a book surrounding that comment, in part, and exposing certain divisions residing in the African American community during the time period of the novel.”

“She told me that if I ever went to Africa, the Africans would kill me. ‘They don’t like no light skinned Negroes in Africa,’ was her assertion. One of my goals was to write a book surrounding that comment, in part, and exposing certain divisions residing in the African American community during the time period of the novel.”

The value of light skin is a reality all over the world, Karen says. There are women in India and various African countries who bleach their skin seeking to achieve one of the “standard” definitions of beauty.

“This phenomenon in the African-American population goes back to the time of slavery and, therefore, elicits more emotion,” she said. “Lighter skinned slaves were usually singled out to work in the master’s house, where the work was not as grueling as work in the fields. Because they were often the result of liaisons between the slave master and his female slave (mostly coerced), they received less harsh treatment.

“In the larger society standards of beauty among African Americans were based on how closely they resembled whites. As a result there was often strong resentment for the more ‘privileged’ light skinned black person. Evidence of this still exists today but not on the scale of what it was historically (at least not on the surface).”

This occurrence was an important element in the book because it governed the relationship between Sophie and Mrs. Baylor, Karen said.

Sophie’s character was based in one respect on Karen’s younger sister, Janice. “I sometimes would come across her sitting on our front porch—waiting it out—when the children on the block went down to a kid’s house where black people were not allowed,” Karen said. “Janice would just read or play with our cat while looking not very bothered about a situation that was simply part of the fabric of America.”

Jennifer, Sophie’s best friend, is white with read hair and a pug nose. She, too, was based on a real person. “She lived directly across the street from us and she was a true friend to my sister,” Karen said. “If she was home during one of these ‘episodes’ she’d choose to be with Janice.”

Karen believes Sophie, not the setting (1965 Los Angeles), is the thing that will resonate with readers.

“I wanted to make her fully realized and relatable,” she said. “Through Sophie, I hoped to give young readers a window into a unique time in black history: that time of transition from apology to pride—and all that went with it. Also, I wanted them to see that black history is an integral part of American history… I want readers to see that we all have the exact same range of emotions. Beneath the superficial, we are all alike.”